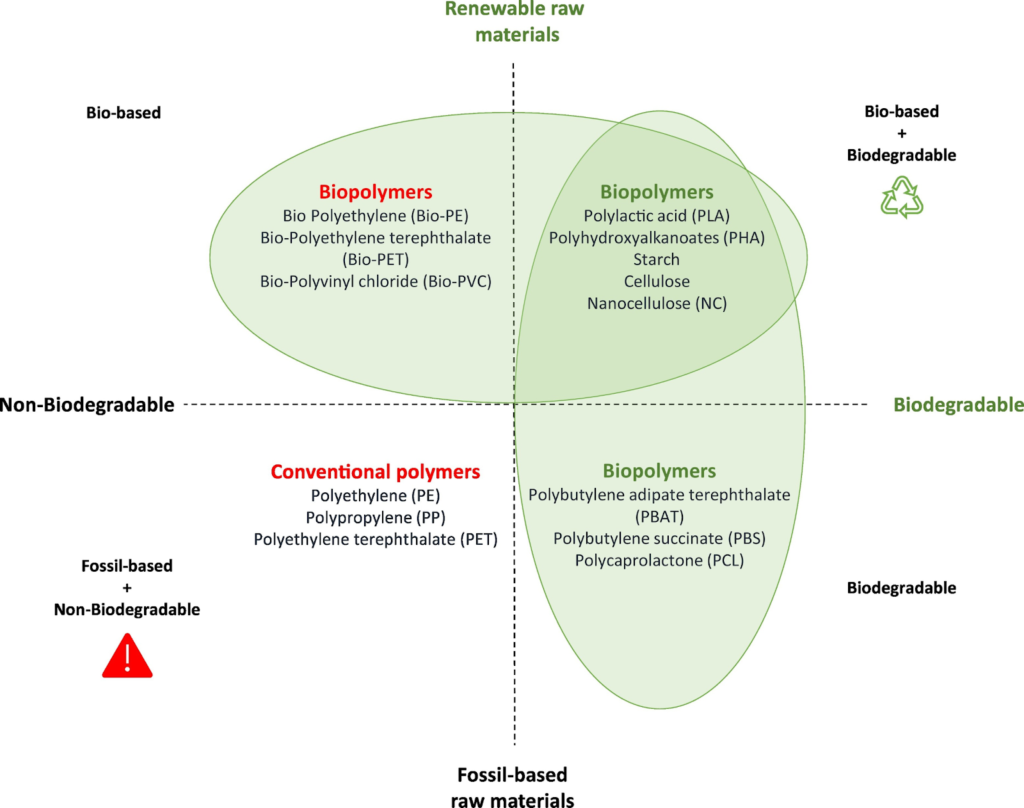

Bioplastics is one of the most misunderstood words in sustainability.

Ask ten people what it means, and you’ll get ten different answers. Some say it’s plastic made from plants, others say it’s plastic that disappears in the soil. But bioplastics can be both or none.

It is a family of materials with three main categories:

- Bio-based plastics (made from renewable resources like plants)

- Biodegradable plastics (can break down naturally, under the right conditions)

- And sometimes, plastics that are both bio-based and biodegradable

Not all bioplastics are compostable and not all compostable plastics come from plants.

In this glossary, I’ll break down the most common types of bioplastics so you can actually understand which is which and what to look out for if you are planning a switch in your material or packaging decisions.

Let’s clear up the first, biggest source of confusion. What is the difference between bio-based, biodegradable, and compostable?

Biobased, biodegradable, and compostable bioplastics

Let’s start with the most popular and perhaps the oldest bioplastic, PLA.

A PLA cup is bio-based and compostable; if it goes to an industrial compost site, it turns into CO₂ and water in under six months.

But a “Bio-PE” bottle is bio-based but not biodegradable. It will last as long as regular plastic if littered.

A third kind of bioplastic item, say a PBAT bag, is biodegradable (even though it’s fossil based) and compostable under EN 13432. But it won’t break down in the ocean.

Here is a table showing the difference between biobased, biodegradable, and compostable bioplastics.

| Bio-based | Biodegradable | Compostable | |

| What it means | Made (partly or wholly) from plants or other renewables | Breaks down by microbes (eventually) | Breaks down in controlled composting, meeting strict standards |

| Example | Bio-PE from sugarcane | PBAT, some fossil-derived | PLA, PBAT, certified blends |

| Regulation | Labels like “bio-based content” (ASTM D6866) | Sometimes, but rarely standardized | Yes: EN 13432 (EU), ASTM D6400 (US) |

This image also explains how bioplastics can be put into three different categories.

What is PLA (Polylactic Acid)?

PLA is what most people think of when they picture green packaging.

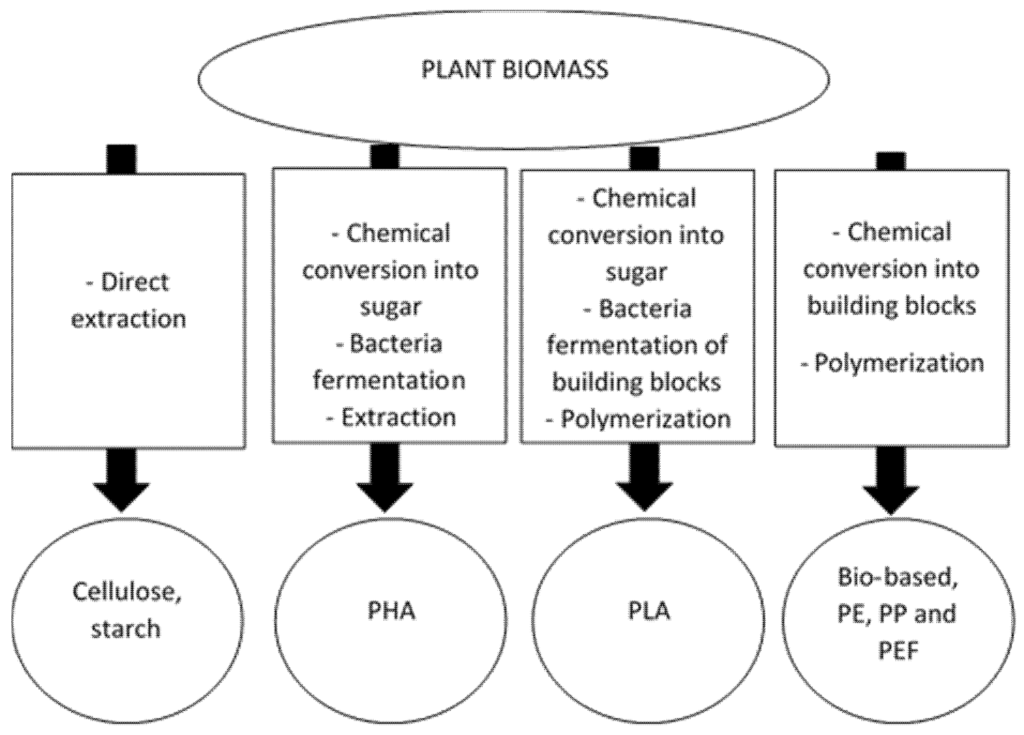

It is made by converting or fermenting the sugars in corn or sugarcane into lactic acid and then polymerizing it. So, basically, turning crops into plastic with a clear finish.

- Strength: Comparable to PET (50-60 MPa), holds its shape, great for packaging.

- Transparency: Looks and feels like traditional plastic, good for food display.

- Limitations: Brittle, can snap if bent, softens at 55-0°C (so hot drinks are a no go).

PLA is commonly used to make disposable cups, deli containers, 3D printing filament and sometimes dissolvable surgical sutures.

Sustainability:

Fully bio-based, compostable plastics but only in industrial composters (high heat, humidity, microbes.

If littered in the ocean or street? It can stick around for years, just like regular plastic.

Regulation:

Approved for food contact in the US (FDA) and EU (EFSA). Certified under EN 13432, ASTM D6400.

But PLA is just the beginning. If you want a material that will break down after getting into the environment, you need to know about PHA.

What is PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates)?

PHA is made by bacteria during fermentation. It is different because it is bio-based and biodegradable everywhere, including in soil and marine environments

Studies have shown that PHA straws degrade in the sea, where PLA won’t.

It is the “gold standard” for litter prone applications like fishing gear and outdoor agricultural films.

But it is still pricier than PLA or PBAT.

Regulation:

Certified compostable (EN 13432)

If you’re looking for compostable plastic bags that stretch and don’t tear, the secret ingredient is often PBAT.

What is PBAT (Polybutylene Adipate Terephthalate)?

PBAT is the hidden hero of compostable bags and flexible packaging.

These flexible bioplastics are as stretchy and strong as LDPE (the plastic in grocery bags).

Origin:

Currently fossil-derived, but bio-based PBAT is in development.

Where is it used?

Grocery bags, garbage bags, mailers, thin films in blends with PLA or starch.

Without PBAT, compostable bags would snap or tear too easily.

Compostability:

Breaks down in industrial composting in less than 90 days. Slower in soil, not marine-biodegradable.

Regulation:

BPI-certified in the US, DIN CERTCO in Europe, and approved for food contact (as part of blends).

What about bioplastics that can handle both hot and cold, and work well in both rigid and flexible uses? That’s where PBS comes in.

What is PBS (Polybutylene Succinate)?

PBS is a ductile, versatile bioplastic gaining momentum globally.

It is made from succinic acid and butanediol, often produced from renewable sources. It’s tough and flexible, meaning it doesn’t get brittle in the cold

PBS is good for:

- Mulch films in agriculture (biodegradable in soil over time)

- Compostable cutlery and plates (usually in blends)

- Flexible and rigid packaging

Compostability:

Meets EN 13432 for industrial composting.

Soil-biodegradable, though more slowly.

Regulation:

FDA-cleared for some food packaging, accepted in the EU.

What is PHB (Polyhydroxybutyrate)?

PHB is one of the earliest known and best studied members of the PHA family, and in many ways, it’s the bridge between conventional plastics and truly natural polymers.

Like other PHAs, PHB is produced by bacteria as an energy storage material during fermentation.

From a sustainability standpoint, that already puts it in a strong position:

- 100% bio‑based

- Fully biodegradable in soil, freshwater, and marine environments

- Breaks down into carbon dioxide and water without leaving toxic residue

From a material perspective, PHB behaves a lot like polypropylene (PP). It is :

- Rigid

- Lightweight

- Chemically resistant

This makes PHB suitable for rigid packaging, bottles, cosmetic containers, and even agricultural products.

However, PHB has one key limitation: brittleness. Compared to PP, it has lower impact resistance and can crack under stress. That is why PHB is often:

- Blended with other PHAs

- Modified with plasticizers

- Combined with materials like PBAT to improve toughness

Cost and brittleness have slowed PHB’s widespread adoption but affordability has driven another category forward: starch‑based plastics.

What Are Starch‑Based Plastics?

Starch‑based plastics are often the most accessible entry point into biodegradable materials and also one of the most misunderstood.

They are directly extracted from natural starch sources, typically:

- Corn

- Potato

- Tapioca

- Wheat

The diagram below shows how starch based bioplastics are differ from PHA, PLA and other bio-based plastics.

Chemically, starch is a polysaccharide, which means microbes already know how to break it down. That gives starch‑based materials a natural advantage when it comes to biodegradability.

On their own, however, pure starch plastics have serious limitations:

- Low mechanical strength

- Poor moisture resistance

- Brittleness in dry conditions

This is why starch is also rarely used alone. It is also always part of a blend with PBAT (to improve flexibility and durability) and PLA (to improve stiffness and processability).

These blends are what you usually see in:

- Compostable grocery bags

- Produce bags

- Lightweight packaging films

- Some food‑service items

Some bioplastics take a very different approach. They reduce carbon without changing how plastics behave.

What Are Bio‑PE and Bio‑PET?

Bio‑PE and Bio‑PET often surprise people because they don’t behave like green plastics.

Chemically speaking, they are identical to conventional polyethylene (PE) and PET. The difference lies only in where the carbon comes from.

Instead of fossil fuels, the carbon in these materials comes from renewable feedstocks, most commonly:

- Sugarcane (in the case of Bio‑PE)

- Plant‑derived ethanol used to produce mono‑ethylene glycol (for Bio‑PET)

Bio‑PE is 100% bio‑based and has the same strength, flexibility, and durability as regular PE. Bio‑PET is about 30% bio‑based and also has the same properties as fossil PET.

These materials are known as “drop‑in bioplastics.” They are recyclable but not biodegradable and can:

- Run on existing manufacturing lines

- Enter existing recycling streams

- Be used in bottles, caps, films, and rigid packaging without any infrastructure changes

From a climate perspective, their main benefit is carbon footprint reduction, not waste elimination. They do not solve litter or microplastic pollution.

FAQs

Can bioplastics be composted?

Not all bioplastics are compostable. Some are bio-based (Bio-PE), others are biodegradable but not bio-based (PBAT). And only those meeting EN 13432 or ASTM D6400 are certified compostable.

What’s the difference between PLA vs PBAT?

PLA is a plant-based and rigid bioplastic, while PBAT is fossil derived and flexible. Both are compostable but serve different purposes.

What are the most important bioplastic properties to check?

When choosing a bioplastic, you must check if its tensile strength, flexibility/elongation, impact resistance, and heat resistance are suitable for your needs. Also check for bioplastic end of life properties like its certified compostability and biodegradability under standards like EN 13432 / ASTM D6400.