The bioplastics market is clearly on a steep growth trajectory.

In 2024, global bioplastics were estimated at around US $15.6 billion. And by 2030 the value is expected to reach US $44.8 billion.

Still, bioplastics are a niche with only about 0.5% of the world’s total plastic production.

What this tells me is that the world recognizes the potential of bioplastics but we’re only scratching the surface.

For a decade, PLA was the classroom example of bioplastics.

But next-gen biopolymers with sharper performance are taking the lead.

Materials like PEF, PBAT, PHA and PBS can be more flexible and sustainable.

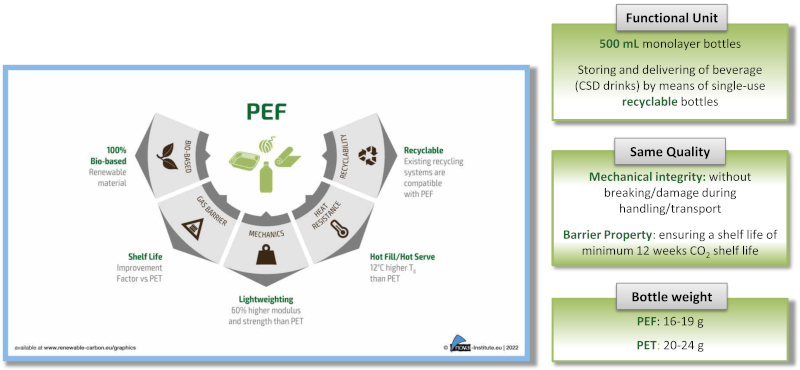

Take PEF bottles, for example.

Compared with conventional PET bottles, PEF offers up to 10 times better oxygen barrier and 16-20 times better carbon‑dioxide barrier. It makes for long shelf life sustainable packaging materials without fossil incumbents.

Or consider PBAT, which is a biodegradable copolymer. It brings flexibility and strength close to what we expect from conventional plastics and is also compostable under certified conditions.

Why is Bio‑PBAT gaining so much attention?

PBAT has emerged as something like the Swiss Army knife of compostable bioplastics and there are several reasons for that.

Flexibility

PBAT is soft, flexible, and resilient, which mirrors conventional polyethylene (PE) more than rigid bioplastics like PLA.

That makes it extremely useful as a biodegradable packaging alternative (films, bags, mulch‑films and wraps).

Compostability

PBAT is a biodegradable copolymer. It breaks down under the right composting conditions.

That gives it a compliance and credibility advantage when brands or regulators demand certified compostable products.

Blending Versatility

PBAT also mixes well with other biopolymers (PLA, starch, even PBS). For example, many compostable bags on global markets are PLA‑PBAT blends.

PBAT’s properties make it one of the most realistic bioplastic substitutes and biodegradable packaging alternatives for conventional plastic items.

That said, PBAT is not perfect. Because it is often fossil-derived, its “bio-ness” depends on feedstock and production route.

Its cost remains higher than conventional plastics. And compostability also depends entirely on proper end-of-life infrastructure.

What are some other next‑gen biopolymers?

Let’s take a short history detour and trace how PLA evolved.

PLA was first made in 1845, when the chemist Théophile‑Jules Pelouze condensed lactic acid into a low-molecular-weight polymer.

Some decades later, chemist Wallace Hume Carothers (better known for Nylon) developed a new method to create a higher-quality PLA.

Still, PLA was too expensive and too weak for mass use until the late 1980s. But by the late 1990s, a joint venture between Cargill and Dow Chemical began commercial production under the brand “Ingeo”.

Now, outside the first‑generation bioplastics, there are multiple next-gen biopolymers that are each suited for different needs.

Some newer bioplastics can offer:

- Flexibility and toughness (PBAT)

- Marine/soil biodegradability (PHA)

- Better heat or mechanical strength (PBS, PEF)

- Compatibility with existing recycling/processing (bio‑PE, bio‑PET)

Let’s learn more about these next-gen biopolymers.

PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates)

PHA polymers are produced by microbes using renewable feedstock. They are bio‑based and biodegradable. These polymers, dubbed the ‘Greenest Plastic So Far’ also degrade in soil or natural environments (not only industrial composting) under microbial action.

That gives PHA a real edge where waste‑management infrastructure is weak.

PHA can also behave like a rigid thermoplastic or a softer elastomer. This flexibility makes it useful for sustainable packaging materials, films and specialty uses.

PEF (Polyethylene Furanoate)

PEF is a 100% bio‑based polyester that is made from plant-derived sugars instead of petroleum-derived feedstocks.

Performance-wise, PEF has been studied to outperform conventional PET on key metrics. This gives it an edge over many first‑generation bioplastics.

It offers up to 2-3 times better water‑vapour barrier than PET and has better thermal stability, which allows for lighter, thinner packaging with lower resource use.

Life‑cycle studies show 50-74% lower greenhouse‑gas emissions in 250 ml PEF bottles compared to PET bottles.

However, it only breaks down in industrial composting systems (58 degrees Celsius) in about a year.

PBS (Polybutylene Succinate)

PBS is another biodegradable polyester that can be partially or fully bio‑based.

Compared with PLA, it offers better heat resistance and mechanical robustness. This makes them useful for food containers or other durable items.

Bio‑based “Drop-in” Plastics (Bio‑PE, Bio‑PP, Bio‑PET)

Drop-in plastics are chemically the same as their petroleum counterparts but made from renewable feedstocks. They deliver the same performance and recyclability but have a lower carbon footprint.

Overall, it is expected that bio-based biodegradable polymers may reach 17% of global bioplastics by 2029. While bio-based non-biodegradable polymers are likely to grow by about 10%.

The image below explains how biopolymers are divided into three main groups:

- First are drop-in bioplastics (Bio-PET, Bio-PE) that are chemically identical to regular plastics. That means you can use them with existing recycling systems and infrastructure. So there is almost zero friction for brands or recyclers to adopt them.

- Second, smart drop-ins (PBAT, PBS) are more efficient or less polluting than old-school methods. They are drawing more attention from both policymakers and investors.

- Lastly, there are dedicated biopolymers (PEF, PHAs, PLA, and starch-based plastics) that have no fossil-based twin. They are designed from scratch for biodegradability.

But not all are biodegradable. You can see that only those with green dots are biodegradable polymers.

So, why does it matter that we have this diversity? Because it lets us match the right polymer to the right need.

- Want a soft, flexible bag for compostable waste? Use PBAT.

- Need rigid containers for food or durable goods? PBS or bio‑PET could work.

- Looking for sustainable packaging materials that degrades in soil or marine settings? PHA shines.

- Want to keep using existing recycling and processing infrastructure while cutting fossil inputs? Drop-in bioplastics are the answer.

At Ukhi, we produce EcoGran from hemp, nettle, and flax residue into granules for packaging and raw material supply. Our next-generation bioplastics create rural income and cut waste at production and supply-chain stages.

FAQs

1. Is PBAT a top choice for sustainable packaging?

PBAT offers more flexibility and toughness than PLA. While both biopolymers are biodegradable, PBAT is better for bags, films and soft packaging where rigid bioplastics fail.

2. What is the main advantage of using PBAT in packaging?

PBAT is a more flexible and durable biopolymer for compostable films. It can also be mixed with other next-gen biopolymers like PLA and PHA.

3. Do next-generation bioplastics change packaging for the better?

Next-gen bioplastics make circular, compostable, and marine-degradable packaging possible. They go beyond PLA to fit real-world applications and global sustainability needs.

4. Is PBAT considered a true biopolymer?

Yes. PBAT is a certified biodegradable polymer. It is often used when compostability and flexible use are main requirements.

5. What’s the latest breakthrough in biodegradable plastics?

Nanofiller-enhanced PBAT and PHA blends offer more strength, thermal stability, and barrier properties for the next generation of biopolymers and food-safe packaging.

6. Which biopolymer is best for marine-safe packaging?

PHA is a better sustainable packaging as it is fully bio-based and degrades even in soil or marine environments.